(From the Cairo Airport Lounge) Returning to Boston from Nazareth, Ethiopia after leading an intensive two-day workshop organized by ENTRO/ENSAP. The theme was Water Diplomacy Framework : from theory to practice with a focus on transboundary water issues. Over sixty water professionals, decision makers, diplomats, and non-governmental actors from the four Eastern Nile countries (Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan) participated in engaging conversations and a spirited transboundary water negotiation simulation game called Indopotamia.

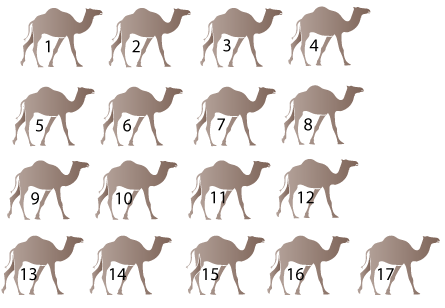

We began the workshop with an age old fable from the Middle East: The 18th Camel. A wealthy man willed his herd of camels to his three sons, allocating half for the first, one-third for the middle, and one-ninth for the youngest son. The man owned 17 camels.

How can you divide 17 camels according to the father’s wishes?

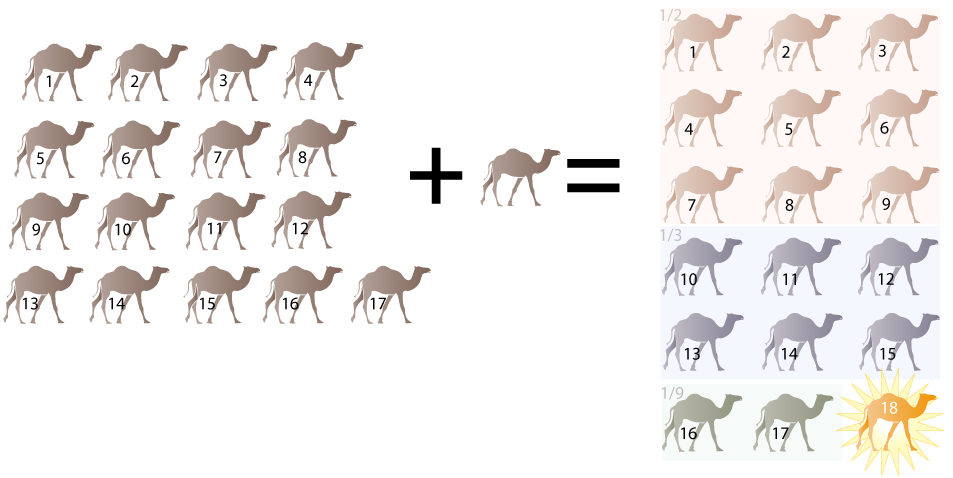

Killing all the camels and dividing the meat may be an optimal solution that could meet the requirements of the will, but it is not a desirable one, as the live camels are more valuable than their meat. One of the sons could concede a portion of his own inheritance to his brothers, but that wouldn’t meet his own interests and would violate his father’s will.

A dispute started among brothers; the feud became heated; cousins were no longer playing with each other; the families were not talking to each other. They couldn’t find a mathematical solution that would meet the requirements of the will and the positions of each brother to get their “fair” share. The problem was unsolvable.

In desperation, brothers visited a wise woman in the neighboring village. After hearing about the dispute, the woman agreed that it was a difficult problem; she would reflect on it, and advise them the next day. The next morning, the woman told the brothers she could not solve the problem, but she would give them her own camel, in hopes that it could help them resolve their problem and end the feud.

The brothers were puzzled, but pleased to have an additional camel, and began to walk home. On the long walk home, they calculated how a herd of 18 camels might be divided. Half, or nine, would go to the oldest, the middle would get a third (six), and after the youngest received his ninth (two), there was still one more camel.

The brothers quickly realized the wisdom of the woman, and decided that they would return the 18th camel to its previous owner, in thanks for helping them solve their problem.

Water Diplomacy is about finding the 18th Camel.

Within the context of Water Diplomacy Framework, we are looking for ways to seek creative resolutions for problems that involve competing user needs. Two key features may help us to find the 18th camel – a pathway for resolving these seemingly intractable problems: (a) the initial formulation of the problem may appear unsolvable; consequently, we need to engage in a problem solving mode with a focus on mutual gains; (b) involving a third party neutral (think of the wise lady) may help reframe the problem to arrive at a mutually agreeable solution.

Where do we see evidence of an 18th Camel in Transboundary Water?

Where do we see evidence of an 18th Camel in Transboundary Water?

Establishment of the Permanent Indus Commission

(1960 Indus Waters Treaty between India & Pakistan)

The Permanent Indus Commission is comprised of a technical expert from each country and they agreed to meet each year (in alternating locations) to examine data and discuss development plans on equal footing. A closer look at the negotiating process of the Indus River Treaty clearly indicates the critical role of a third party (World Bank and US Government) in facilitating the agreement. The autonomy of the commission and the strong dispute resolution mechanisms built into this agreement helped to alleviate the symptoms of mistrust that were preventing agreement over water sharing.

Water apportionment for the Jordan

(1994 Israel Jordan Treaty of Peace)

This agreement allows Jordan to store 20 mcm of water in Lake Tiberias ( Kinneret) in the winter and have that amount transferred in the summer. The need for water is as much about timing as it is about quantity. The agreement further specifies “the quality of water supplied from one country to the other at any given location shall be equivalent to the quality of the water used from the same location by the supplying country” to address some of the trust concerns over the storage and transfer of shared water.

Clearly, these are highly simplified examples of years of negotiation and the details of the agreements. The groundwork for building trust and agreement may have developed over many informal problem-solving and joint fact finding session between Jordanian and Israeli technical experts spanning the years between the “Johnston Plan” and the “Treaty of Peace” and contributed to the design and longevity of the 1994 agreement. The Indus Waters Treaty divides the rivers, rather than the water within them, and wouldn’t have been enacted without significant outside funding to support necessary water transfers that made the division feasible. Even with messy and imperfect resolutions, infusing creative flexibility in institutional or resource sharing arrangements can produce more value for the parties faced with competing and conflicting needs for water. Please post comments and share other examples of creative resolutions that we’ve missed mentioning here.

There have been other water problems that were once seemingly intractable, but the identification of creative options and opportunities to create flexibility in agreements allowed for the identification of pathways to resolution. Elements of the Indus Waters Treaty and the Israel Jordan Treaty of Peace produced the flexibility needed for water resource sharing agreements that have endured even with mistrust and conflict between the respective signing countries.

How do we find the 18th Camel for the Nile?

The Nile is as old as human civilization. Over thousands of years, it has continued in its course, deeply embedded in the cultures, histories, myths, mistrust and wars of the people who have depended upon it. This deep history and reliance upon this resource to support past, current, and future water needs contribute to one of the most intractable hydropolitical situations of our time. In our water diplomacy parlance for the Nile – natural, societal, and political processes and variables are intricately linked – no clear solution is apparent with the current framing. Without an 18th camel for the Nile, the problem is unsolvable.

Finding creative solutions to address multitude of water issues in the Eastern Nile isn’t going to happen in a single workshop, but after two-days of sharing and learning together in Nazareth, we all agreed that together we must look jointly to find the 18th camel for the Nile with three guiding ideas:

First, water is a flexible resource, and flexibility can be created many ways. We need to work jointly to find what those flexible solutions might be for the Nile.

Second, our joint problem solving will focus on interests, not positions.

Third, we will look for mutual gains solutions with the understanding of the complexity and uncertainty associated with availability, access, and allocation of the resources related to the Nile.

The problems experienced in the Nile are not entirely unique. Other large transboundary basins have competing and conflicting needs for water between upstream and downstream stakeholders. Many countries are examining how they can improve their access to clean energy, such as hydropower, and balance water needs for energy, ecosystems, agriculture, and livelihoods. Creative approaches and mutual-gain solutions can be found, and the 18th camel we seek for the Nile may, like the wise woman’s own camel, be creatively shared and contribute to solutions for other complex water problems.