The question of whether and how to harness rivers for irrigation, hydropower generation, urban development and sustainability of ecosystems continues to be an issue of great concern, conflict, and cooperation for this region. While pessimistic speculation on the endemic nature of water stress within and between countries in South Asia occurs commonly, there is a void of suggestion on what to do next.

We need informed conversations to hammer out the details required to act and move forward on how to develop and share the Himalayan rivers for an equitable and sustainable future. Complexity of transboundary water issues demands learning from other river basins – like the Nile, Jordan, and Danube – and adapting to local situations. Interconnectedness and interdependence of issues as well as competing and conflicting values and priorities for water allocation make the process of charting a path for the future difficult.

Who decides? Who benefits? Who bears the burden? These difficulties are amplified by practical questions: how can we reconcile India’s water needs for development with the need for adequate water supply and to minimise salinity intrusion during the dry season for Bangladesh? As water demands increase, how will countries meet previous water agreements? While preventive diplomacy has kept conflicts at bay, it is now time for water diplomacy to strengthen the bonds of cooperation.

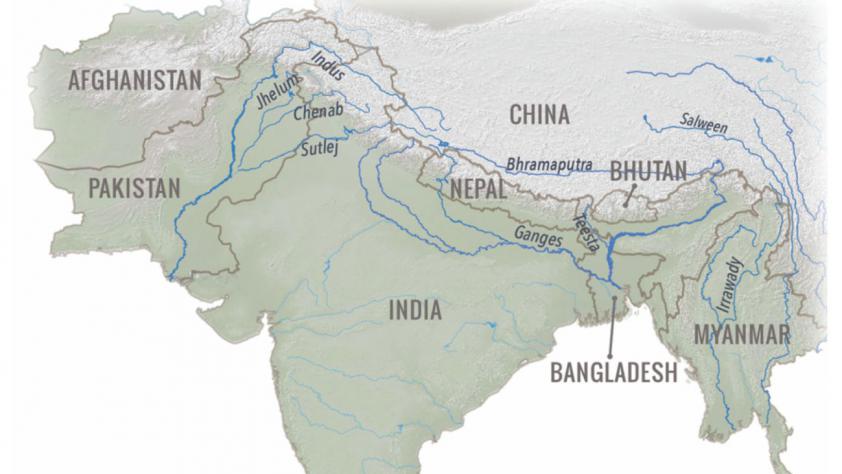

Major rivers of South Asia with origins in the Himalaya and Tibetan Plateau.

These water questions are contingent upon the context, framing, and choice of the problem’s scale and scope. Consequently, there are no pre-specified solutions. To develop actionable strategies with mutually beneficial options, a different approach is needed. The Water Diplomacy Framework – developed by a global group of academics and practitioners led by faculty from Tufts University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University – is a step in that direction.

An example of implementation of a mutually beneficial option is in the 1994 Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty that includes an agreement regarding water sharing across borders. The treaty specified that Israel could extract twelve million cubic metres (MCM) of water during the summer and thirteen MCM in the winter from the Yarmouk River. In exchange, Jordan stores twenty MCM in Lake Tiberias in Israel during the winter, to withdraw when it is needed in the summer months. Israel agreed to help Jordan find additional water through desalination which dovetailed with Israel’s long-term desalination programme. Technological and scientific creativity facilitated this water agreement. Although the agreement was bilateral, excluding other riparian entities, given the regional political dynamics, it was still a remarkable accomplishment.

One way to explore mutually beneficial options is the Devising Seminar – conceived at the Programme on Negotiation at Harvard University – a professionally facilitated problem-solving forum that includes individuals covering a wide range of stakeholders. This provides a facilitated process to discuss interests of all key stakeholders and generate ideas that meet the interests of all parties. None of the ideas generated are attributable; participants can focus on finding solutions that meet everyone’s interest, rather than only considering those that reflect a specific political agenda. The process does produce formal agreements, so participants explore options without commitment, suggesting evidence-supported actions that could gain the support of most, if not all, the stakeholders.

Devising Seminars can take many forms but include some common required elements: (a) a prepared synthesis of current knowledge, issues, and controversies – including technical, societal, and political – surrounding the Himalayan water issues from multiple perspectives; (b) a Stakeholder Assessment comprised of one-on-one, off-the-record interviews with a wide range of individuals – including representatives of government entities and organisations involved in the dispute, as well as technical and scientific experts who can provide well-informed perspectives on what is known and not known about the issues. All information remains anonymous and unattributable; (c) Skilled facilitation by a professional neutral is critical. The facilitator has to create and maintain a space in which all parties can think creatively and work together to envision new options; (d) A Devising Seminar provides confidentiality following the Chatham House Rule and is organised without observers or media present. The facilitation team takes notes throughout the workshop; however, nothing is attributed to any individual, and participants are not identified in any of the workshop materials. This private forum creates a setting in which participants can think out loud and consider new ideas. It can allow participants to put aside their typical party lines and explore creative options, without fear of retribution from higher decision making authorities.

A final element of a Devising Seminar is the preparation and dissemination of a summary report. This report shares key ideas and points of agreement that emerge from the discussion. It can take many forms, from a single page memo directed to a specific group, to a more general summary that can be shared broadly. The Summary Report is actionable because the ideas are generated through collaborative problem solving and stakeholders have the confidence that these options are likely to generate widespread support.

To explore the effectiveness of a Devising Seminar for the Himalayan rivers, it may be worthwhile to convene such a seminar among stakeholders from India and Bangladesh with a focus on the Teesta, Ganges, and Brahmaputra and develop a summary of creative options – guaranteeing issues of sustainability and equity – by linking multiple issues and creating mutual gains for both countries.

A version of this post first appeared in The Daily Star